My 2025 reflections on 42 science fiction, fantasy, and speculative works exploring systems, consequences, and the moral frameworks that shape thought and action.

I don’t read books for escape. I read them for orientation. I wander to find my bearings.

Experience teaches you that events rarely speak for themselves. Meaning emerges through framing, context, scale, and what endures after the moment has passed. Speculative fiction has always helped me see those structures more clearly. By bending reality just enough, it exposes the systems underneath.

In 2025, I spent most of my reading life immersed in speculative fiction — science fiction, fantasy, sword and sorcery, and mythic narratives that function less as entertainment and more as tools for thinking.

This isn’t everything I read, but it’s the arena I returned to most often.

Some of these books I read in physical form. Some I listened to. Others, I moved between text and audio, sometimes at the same time. Dyslexia complicated reading early in my life; narration isn’t a shortcut — it’s an access point. A strong performance doesn’t just transmit story. It reveals rhythm, intention, and emotional weight that can otherwise stay buried.

By the numbers: 42 books, ~18,000 pages, ~7.6 million words.

Not the count, but the focus, that mattered.

Why Speculative Fiction

Like all nerds, we must defend! Speculative fiction strips reality down to its load‑bearing elements, exposing the structures that shape thought, choice, and consequence.

Remove familiar geography, contemporary names, and inherited assumptions, and what remains are structures: power, belief, obedience, memory, myth. Fantasy and science fiction make visible what realism often leaves implicit. Empires have edges. Hierarchies are formalized. Consequences echo across generations.

Sword and sorcery, at its best, reduces morality to consequence: what power costs, who pays, and what remains afterward.

These genres don’t simplify the world. They widen the reader’s lens. They slow judgment and sharpen perception. They change scale — and scale changes meaning.

The Shape of the Year

Across decades and subgenres — from Jack Williamson’s The Humanoid Touch to Ada Palmer’s Terra Ignota, from Tolkien’s mythic histories to Butler’s near‑future collapse — the same questions kept resurfacing:

How do systems shape behavior before choice feels possible?

What happens to ethics when scale outpaces intimacy?

When does obedience harden into abdication?

How do people construct meaning without guarantees?

This wasn’t a year of triumph narratives. It was a year of aftermath, memory, and consequence.

Systems, Not Heroes

Many of the books that anchored the year are deeply skeptical of individual heroism.

C.J. Cherryh’s Cyteen is one of the most intellectually rigorous novels I’ve read. Identity, loyalty, and consent are revealed as artifacts of institutional design — no villain is required; the system itself produces consequence and operates as indended. Events from Forty Thousand in Gehenna echo throughout Cyteen, providing both context and moral contrast, showing how decisions compound across generations and how societal structures shape behavior. Reading Forty Thousand in Gehenna after Cyteen was essential: it illuminates the consequences that Cyteen examines in theory, making the stakes of political manipulation, social engineering, and cultural drift visceral. The Faded Sun Trilogy (Kesrith, Shon’jir, Kutath) extends these themes across alien societies, where honor becomes a survival language and misunderstanding fossilizes into tradition. The Faded Sun begins in conversation with Dune but quickly moves into its own lane: dry, stark, and anti‑epic.

Ada Palmer’s The Will to Battle imagines governance without shared moral ground, where ideology fractures under scale and politics becomes procedural rather than ethical. Laws, rituals, and bureaucracies persist even as underlying justice dissolves, showing how societies can operate efficiently while remaining morally unmoored. James Islington’s The Will of the Many and The Strength of the Few explore similar terrain, depicting societies built on extracted obedience, where sacrifice is normalized and dissent carries structural penalties. Both authors probe the tension between individual agency and systemic constraint, revealing how power, ideology, and ritual shape behavior and consequence.

Steven Erikson’s Fall of Light and Ian C. Esslemont’s Forge of the High Mage trace the slow petrification of myth, ritual, and sanctioned violence into law, doctrine, and unquestioned authority -long before necessity demands it. Across the twenty-five, twenty-six volumes of Malazan: Book of the Fallen, acts born of pragmatism fossilize into tradition; gestures meant to solve immediate problems ossify into creeds that govern belief, behavior, and power. Violence morph with law, ritual weaves into hierarchy, repetition alone spawn authority, indifferent to ethics or mercy.

To read the series in full is to feel the cumulative weight of memory, consequence, and systemic logic pressing against the spine. The world is vast, intricate, and brutal. Patterns surface; small choices echo across centuries and its famously extensive dramatis personae (Latin, literally ‘persons of the drama’). The machinery of society grinds forward, often cruelly, always inexorably.

I petition all readers: bear witness. Malazan is a masterclass in the human cost of enduring systems, reshaping how we perceive complexity, scale, and moral consequence — not only in fantasy, but across all speculative worlds.

These books share a fundamental insight: systems don’t need malice to produce harm. They need time, continuity, and participation.

Unreliable Narrators and Limited Truth

Many of the my favorite reads this year are told through fractured or constrained perspectives. Piranesi was one of these stories, and the one I gifted the most. The narrator isn’t so much unreliable as constrained, navigating a world that limits knowledge, memory, and perspective. What is lost in recollection is regained through attention, ritual, and care — the small acts that give life structure and significance. Gentleness becomes adaptation, and curiosity becomes survival. Clarke’s prose transforms a solitary, meditative story into a reflection on resilience, the persistence of understanding, and how humans create coherence even when reality refuses to provide it. The work underscores a central insight of speculative fiction: that structure and understanding — whether in labyrinthine halls or across galaxies — are human inventions, forged through care, ritual, and persistence.

Gene Wolfe’s Shadow & Claw demands patience. If you’ve tried to read it you know. Language obscures as much as it reveals, and the story rewards careful attention. Truth dissolves not through deception, but through ritual, forgetting, and the imperatives of survival. Wolfe constructs a world where memory, perspective, and interpretation are as much a part of the narrative architecture as plot. Where understanding is earned, often slowly, through reflection and engagement with the text’s layered complexities.

Shadow Upon Time arrives when remembrance is no longer a gift but a weight. As the final tome of Christopher Ruocchio’s Sun Eater, understanding does not precede consequence — it trails it, creeping in only after history has carved its mark. Where lesser stories lean on deus ex machina (Latin for “god from the machine”), here divine intervention, religion, and myth feel earned, woven into consequence rather than convenience. Sun Eater is not grand for scale alone, Reader; it is grave because it teaches that meaning comes after harm, never before.

Across these works, objectivity matters less than coherence. The self doesn’t need to be accurate to endure — it needs to be livable.

Adaptation, Change, and Prescience

Octavia Butler sits at the philosophical center of this reading year.

In Parable of the Sower, belief evolves because it must. God is Change, not comfort but discipline. Parable of the Talents shows how belief hardens under pressure, how faith becomes an institution rather than a refuge. Butler in 1998 gives her authoritarian demagogue the slogan “Make America Great Again,” and the force of the moment is not the words themselves, but the structure behind them. She understands how nostalgia becomes governance, how fear reorganizes institutions, and how violence is reframed as moral restoration.

Kindred collapses time to show that history lives not in archives but in bodies. Trauma is inherited, reenacted, and normalized through survival. Dana’s repeated returns are not lessons learned but injuries endured; knowledge offers no immunity. The novel refuses distance. The past is not past—it asserts itself through flesh, through power dynamics that persist even when recognized.

Imago closes Xenogenesis by refusing nostalgia altogether. The trilogy begins with survival and negotiation; it ends with irreversible change. Consent is renegotiated, humanity is no longer centered as the default measure of value, and continuity gives way to divergence. The future Butler imagines is neither conquest nor extinction, but change so complete that return is impossible. What survives is not purity, but adaptability.

Butler does not console.

She clarifies.

Myth, Memory, and Voice

In The Silmarillion, Tolkien treats myth as moral technology. Creation begins as gift and gradually collapses into possession, control, and obsession. Loss accumulates slowly, across ages, until it feels not sudden but inevitable. Power is rarely seized outright; it is inherited, misused, and rationalized over time.

Andy Serkis’s narration brings an emotional clarity and physicality that make these ancient stories feel less distant and more lived-in. Even though I read The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings last year, experiencing Serkis’s narration of The Silmarillion made staying in Middle-earth feel essential. His command of cadence, character, and restraint is a reminder that voice shapes meaning, especially in dense or mythic prose. In Tolkien’s work, narration becomes a form of interpretation, revealing how myth survives not just through text, but through performance, memory, and retelling.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea cycle (A Wizard of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan, The Farthest Shore) provides a counterpoint to the scale-driven epics elsewhere in my reading. Through restraint, balance, and acceptance of limits, Le Guin shows that wisdom often comes not from conquest or accumulation of power, but from understanding one’s place within a system. Her Hainish novels — Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile, and City of Illusions — examine how myth, cultural misunderstanding, and incomplete knowledge shape destiny across generations. In both cycles, she demonstrates that the consequences of actions extend beyond the individual, that societal structures and inherited narratives profoundly influence behavior, and that survival and ethical clarity require attentiveness to context, history, and perspective.

History, these books suggest, endures not as record, but as story, carried forward through memory, myth, and the choices of those who live it.

Violence, Authority, and Scale

Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers asks whether discipline and violence can be morally formative, whether civic virtue can grow through obedience and shared sacrifice. I watched this a dozen times on my first military deployment. “I need a corporal. You're it, until you're dead or I find someone better.” The book is quieter, more precise, asking: can structured duty and exposure to controlled violence teach ethical clarity, or does it simply normalize conformity and numb the individual? Read alongside Butler, Palmer, and Cherryh, the question doesn’t resolve; it deepens. In Cyteen, loyalty and identity are engineered; in Terra Ignota, ideology fractures under scale; in Butler’s Parable series, ethics are a daily negotiation. Discipline and duty are not inherently virtuous; their meaning depends on context, scale, and the consequences of obeying flawed or indifferent systems.

Michael Crichton’s The Lost World and Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep explore intelligence without wisdom and scale without restraint. Progress accelerates collapse when ethics lag behind capability. Crichton’s world collapses under human hubris, showing the cascading cost of choices made without foresight. Vinge imagines a galaxy divided into zones of thought — where intelligence and technology ebb and swell under cosmic law — reminding us that knowledge, power, and ethics are never separate, and consequences are magnified across civilizations.

Ryan Cahill’s The Bound and the Broken — Of Blood and Fire, Of Darkness and Light, Of War and Ruin, Of Empires and Dust, along with The Fall, The Exile, and The Ice — refuses tidy victories. War does not end; it reshapes suffering, leaving trauma as a persistent force that molds choice, character, and society. Of War and Ruin and Of Empires and Dust together articulate the cost of power with rare emotional clarity. I love taking long walks while listening to epic fantasy, and this series delivers it at its fullest: dragons, magic, sword and sorcery, lore, and fully realized worlds. Derek Perkins’s narration mirrors the story’s weight and scope, carrying the listener through victories, defeats, and the quiet aftermath.

These works remind me that the stakes of power, obedience, and violence are never abstract. Across battlefields, alien civilizations, and sprawling interstellar societies, every choice reverberates through lives and systems. Scale amplifies consequence, and morality is forged not in isolation but in the friction between duty, systems, and the human cost of action. These are the books that make me consider not just the story, but the architecture of consequence itself.

Small Books, Heavy Gravity

A Short Stay in Hell is brief, but immense. It uses scale to erode meaning, forcing purpose to be chosen without rescue. The Humanoid Touch questions whether humanity is defined by empathy, intention, or behavior, exploring the subtle ways we fail or sustain one another. Merchant’s Luck examines agency under asymmetrical power, showing how survival is rarely a matter of fairness but of navigating complex, unequal systems. The Farthest Shore confronts entropy and the limits of magic without spectacle, a meditation on endings and the moral weight of intervention.

These books linger not because they resolve their conflicts, but because they refuse to, demanding that the reader inhabit uncertainty and consider the consequences that ripple beyond the story.

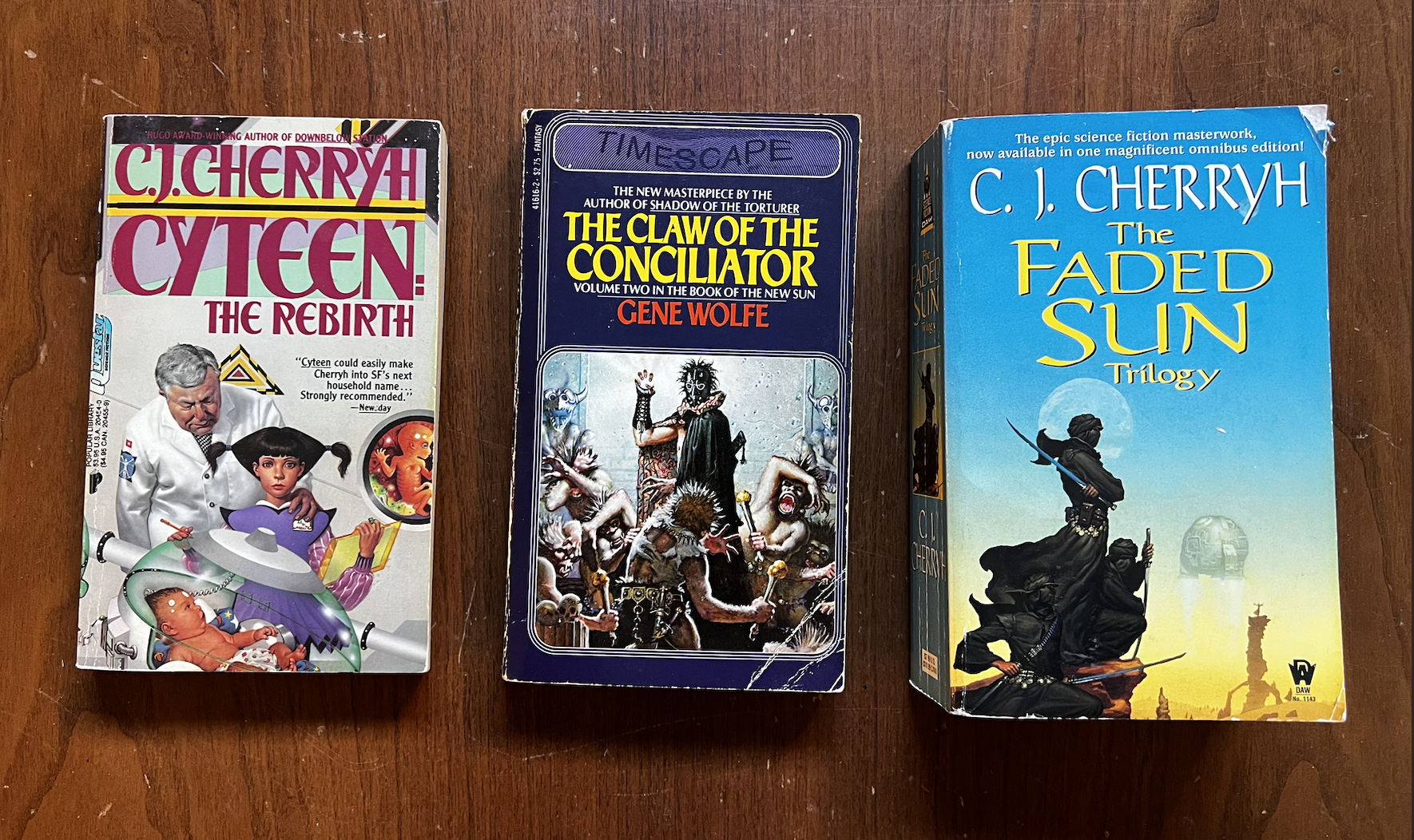

The Physical Object

The cover art drew me into speculative fiction. Beyond the physical object, aesthetics, architecture, mood, technology, weapons, creatures, symbols, and environments often speak as powerfully as plot or theme. For me, design works in two distinct but connected directions.

First, the physical book itself. Cover art, typography, layout, paper, binding, and even the title shape expectations before a word is read. At its best, a book becomes an artifact — meant to be handled, revisited, and kept — reinforcing the weight and permanence of the ideas inside. At its worst, generic design can undersell complexity, creating dissonance between presentation and substance.

Second, the worlds themselves. From the ritual-bound halls of Earthsea to the institutional architecture of Cyteen, the collapsing suburbs of Parable of the Sower, or the infinite spaces of Piranesi, environments are suggested, not exhaustively rendered. Great authors give just enough for the reader to construct their own vision. That restraint invites participation: the author provides structure, the reader supplies texture, memory, and meaning. When it succeeds, the world feels lived-in, discovered rather than explained.

Story, Character, and Growth

Speculative fiction is often measured in terms of scale - worlds, systems, big ideas. What’s easier to miss is how easily that scale can eclipse the personal. The books that stayed with me resist that imbalance. They use the macro not to replace interior life, but to test it.

In Piranesi, growth is not accumulation but integration. The protagonist becomes someone new —neither who they were nor who they are — learning to live with knowledge that cannot restore what was lost. In Cyteen, character is inseparable from design. Identity is shaped, constrained, and reproduced, raising the unsettling question of whether growth is possible inside systems that engineer desire, memory, and loyalty. In Kindred, growth is brutal and embodied. History does not educate from a distance; it marks the body, reshapes relationships, and makes survival morally expensive.

Even within epic frameworks — The Bound and the Broken, Sun Eater, Malazan — growth is not measured by power gained, but by what characters are forced to endure, relinquish, or carry forward. Trauma does not resolve cleanly. Moral clarity arrives late, if at all. The best parts of coming-of-age tales are less about triumph and more about learning what cannot be fixed and choosing how to live anyway.

These stories suggest that speculative fiction’s deepest work is not prediction, but orientation. They map how people change under pressure — ideological, cosmic, institutional, or historical — and ask what remains when certainty collapses. Growth here is not comfort. It is adaptation, responsibility, and the slow construction of meaning under constraint.

Best of the Shelves

Piranesi, Cyteen, Shadow Upon Time, Of War and Ruin / Of Empires and Dust

My favorite stories this year share a refusal to rescue the reader.

Hope, here, isn’t optimism.

It’s discipline.

This year’s reading was more clarifying than comforting.

Reading didn’t make the world simpler.

It made it legible.

And that feels like the point.